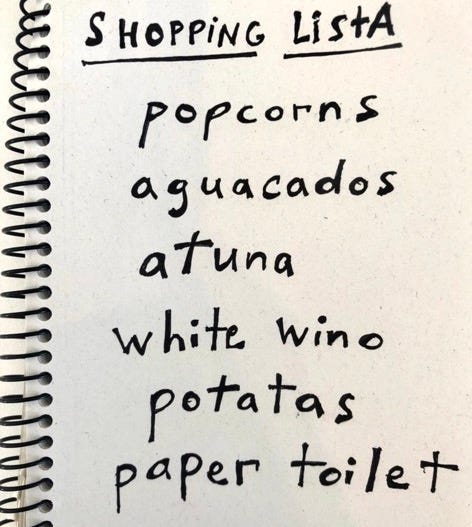

After fifteen years in Andalusia, I can’t be sure my Spanish has gotten better—only that my English has gotten worse. Exhibit A:

Let’s have a look:

“List” in Spanish. More and more I find myself beginning a word or expression in one language and finishing it in the other. I recently referred to the moon not as the moon or la luna, but “the moona.” Instead of hasta luego, or “see you later,” I once said hasta lu-ater. Early in the morning, before I’ve had my caffeine, I’m liable to refer to the beverage that will deliver it not as coffee or café, but “co-FAY” (or “CA-fee,” which just sounds like I’m from Boston.)

In Spanish as in English, “corn” (maíz) is not countable. Just as in English you might eat “a lot of corn” and not “a lot of corns,” in Spanish you might eat mucho maíz and not muchos maizes. But as soon as you pop that corn in Spain, it splits into countable palomitas—literally, “little pigeons.” When I write POPCORNS, I’m applying Spanish grammar to an English word. On the grocery list, the same thing can happen with CEREALS and BROCCOLIS, both of which are countable in Spanish. Outside of the grocery list, it can happen with GASES, as in Forgive me, mi amor. Those broccolis gave me gases.

Here I’m inadvertently fusing the Spanish aguacate with the English avocado. Anymore, I am much more likely to say “aguacado” or “avocuate” rather than aguacate or avocado, and to struggle when pressed to cite the actual word in either language.

The original Spanish word, ATÚN, joined at the last minute by the English version, TUNA.

No comentario.

You say patata, or maybe potato. I say potata, or sometimes patato.

Which is to say, toilet paper. In Spanish the thing you’re describing usually precedes the description of it. Just as “white paper” is papel blanco and “recycled paper” is papel reciclado, “toilet paper” is papel higiénico. Word order in English has always been a challenge for my younger students; anymore, it’s a challenge for me. Like “popcorns,” PAPER TOILET is the sort of mistake I routinely correct in the classroom and increasingly make outside of it.

And so it is that my native English—the language I’ve been eagerly reading, writing and teaching for the better part of my life—doesn’t sound quite so native anymore. That might be easier to accept if I thought my Spanish were getting any better in the bargain, but I’m not so sure it is. What’s happening feels more like a linguistic do-si-do*: as I nudge the Spanish out of my students’ English, it finds a new home in mine.

*Itself an adaptation of the French dos-à-dos, or “back to back.”

Loved this. Dare I say that this is an early stage of a variation of Iberian Euro-English.