English spelling is famously bonkers. The same set of letters can produce totally different sounds (through, dough, enough), while different sets of letters can produce the exact same sound (to, two, too). In contrast, Spanish spelling is mercifully logical. With very few exceptions, each letter corresponds to a particular sound. If you want to spell an “o” sound, you write “o”; if you want to spell a “u” sound, you write “u.” If you want to spell your teacher’s name, you write:

In Spanish the letter “i” makes an “ee” sound—and only an “ee” sound. Around here, wi-fi is pronounced “wee-fee,” and Spiderman is pronounced “speederman.” The English loanword “freaky” is pronounced “freaky”—but spelled friki. Consider the name of this boutique, just up the street from the flat I rented when I first moved to Spain back in 2007:

The first time I saw “Pick Ouic,” I saw English and French, and I read something like “pick week.” It wasn’t until I heard my EFL students saying “sheep” for ship and “free-day” for Friday that I figured out what I was missing. Read in Spanish, Pickwick sounds like “peek-week.” Pick Ouic, then, is a clever bit of wordplay that manages to squeeze three languages—English, French, and Spanish—into two words. The Spanish is in the pronunciation. There’s no real danger of a local missing the wordplay, because again, the “i” can make only one sound in Spanish. In fact, the short “i” sound in English words like “pick” is not even part of the language. EFL students who don’t learn to say it at a young age tend to have a hard time with it. If you’ve ever struggled to produce the trilled “r” in Spanish, you can sympathize.

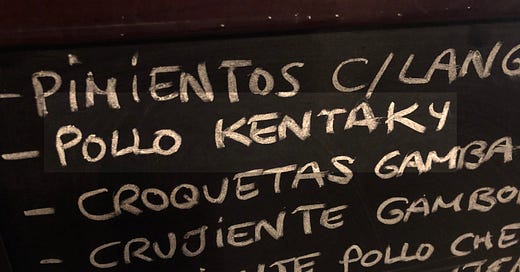

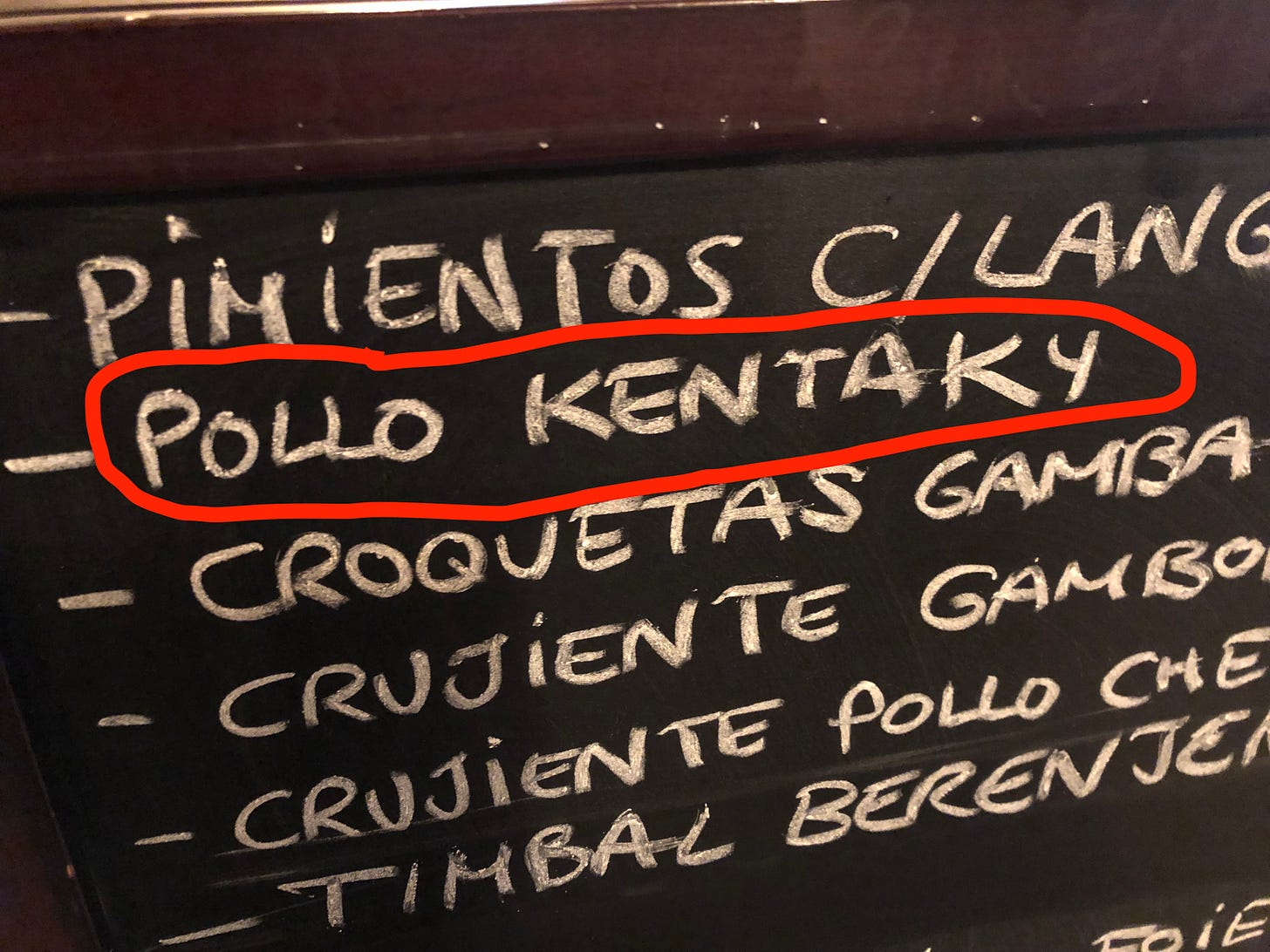

Another sound that can cause grief for EFL students in Spain is the short “u” in words like hut and tough. The closest you can get to that sound in Spanish is “ah,” represented by the letter “a,” for which see:

Pollo Kentaky is not, as I first imagined, some kind of Asian poultry dish, á la chicken teriyaki. Pollo Kentaky is “Kentaky Chicken,” which is to say, “Kentucky Chicken.” If you order the Pollo Kentaky but don’t finish it, you can take the leftovers home in “un táper,” which is to say, “a Tupper,” which is to say, a Tupperware.

Should all this seem weird, funny, and/or just plain wrong to you, bear in mind that English has been having its way with Spanish words for centuries. English swallowed juzgado (courthouse) and spit out “hoosegow.” El lagarto (the lizard) morphed into “alligator,” estibador (one who stows) into “stevedore.” In the States we pronounce Spanish loanwords like guerrilla and vigilante in ways that render them utterly unrecognizable to the very people we borrowed them from. The Toledo in Spain—the original Toledo—is pronounced something like “toe-LAY-tho.” The one in Ohio is…not.

Fifteen years on, I’ve gotten better at spotting English in the wild. I’ve learned that when a word doesn’t ring a bell in either my first or second language, it may well be a cocktail of both. (A cóctel, as it were.) I read mítin, and I hear “meeting.” I read líder, and I hear “leader.” Occasionally, though, the conventions of my native language blind me to the fun my adopted country is having with it:

Was this British English, in which a “bum” is a rear end? Did BUM FM perhaps play a lot of booty-shaking funk? Well, no. Contemporary pop, as it turns out. If you can shake your behind to it, that’s coincidental. Around here, BUM goes BOOM.

Is this applicable to all Latinate languages? It seems a useful lesson with broad use.