Fish in a Barrel

Thoughts on a loaded language

Of the many guns-and-ammo idioms an English teacher may be asked to unpack, “as easy as shooting fish in a barrel” is a particularly curious one. Is shooting fish in barrels a thing that was done at some point in history? Is this something folks used to get up to when they were bored on a Saturday afternoon? Figurative expressions don’t come out of nowhere. People create them. Even if our forebears never passed the time shooting actual fish in actual barrels—and I can’t find any evidence that they did—somebody must have imagined doing it1.

Some guy named Jimmy, let’s say. Jimmy’s sitting around the fire plotting a bank heist with his buddies, and he thinks to himself, This is going to be as easy as taking a big barrel, filling it with water, dropping some fish in there, and shooting them. “Fellas,” Jimmy says, “this job is going to be as easy as shooting fish in a barrel.”

At this point, Jimmy’s buddies might have asked him if he was feeling okay. They might have even sought help for Jimmy. But they didn’t. No. They reckoned shooting fish in a barrel would, in fact, be easy—and then they started using the expression, too. Today, these many years later, anybody might use it. Even a vegan, who wouldn’t so much as inconvenience an actual fish, might reference shooting a figurative one in a barrel.

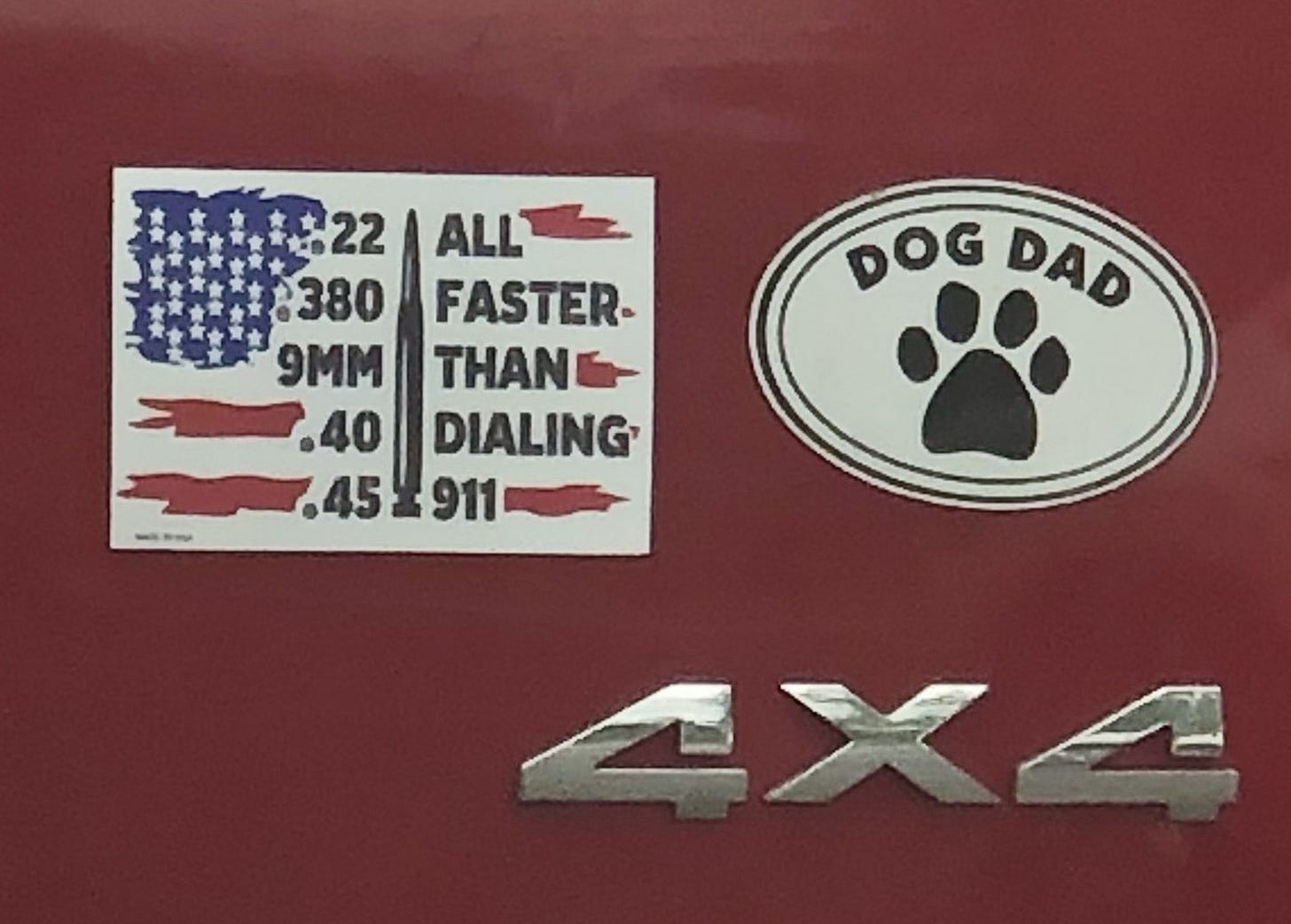

The fact is, in American English you can hardly open your mouth without opening fire. Where I’m from you can shotgun a beer in the shotgun seat on your way to a shotgun wedding in a shotgun shack. You can take a bullet, dodge a bullet, and/or bite the bullet. You can sweat bullets. You can wish you had a silver bullet to use as a magic bullet, and if you want to make an argument bullet proof, you can use bullet points.

You can jump the gun, pull the trigger, take the flak. You can shoot the messenger when you’re shooting the breeze; you can shoot yourself in the foot if you shoot from the hip; and if you want to give someone else a shot, you can say, Go ahead, shoot.

You can be quick on the draw and quick on the trigger. You can spike your guns, flex your guns, stick to your guns. You can bring out the big guns. You can go great guns. You can go ballistic, drop f-bombs, get hotter than a 2-dollar pistol. Shoot—you can even be a pistol.

You can be a big shot. You can be top gun. You can be a loose cannon with a hair-trigger temper who goes off half-cocked. You can come at me full-bore, with all barrels, loaded for bear, at which point I might feel outgunned, under the gun, and/or like I have a gun to my head.

Whether you find these expressions clever, grotesque, or a little of both, they’re hardly surprising in a language that was forged on the frontier, where a gun could mean the difference between eating and being eaten. More puzzling, maybe, is the fact that while the frontier’s long gone, the guns are still there—not just in the language but on the nightstand, under the bed, and next to the armchair; in the sock drawer, above the mantel, and behind the sofa. An English teacher could base an entire prepositions-and-furniture class on the assorted places Americans keep their 390,000,000 some-odd guns.

Bear that in mind the next time a polarization profiteer makes a casual call for civil war from the safe remove of a social media account. Building a democracy is hard, hard work. Tearing one down by playing to the basest instincts of a heavily armed citizenry? Fish in a barrel.

Not that we’re not capable. The erstwhile pastime of bear baiting, for example, involved setting attack dogs on a bear chained to a post. Here in Andalusia, bull “fighting” is still broadcast on public TV.

“Hit me with your best shot, fire away!”

This was great to listen to. Nice to hear your voice!